My Mental Health Journey: Reflections from India by Ritika Mahajan

Feb 2

7 min read

0

0

0

3 March, 2023

India stands fourth in the number of PhDs awarded annually. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Report, 27000 candidates completed a PhD in India in 2017. This number is equal to 10 per cent of the total PhDs across G20 nations. Between 2011 and 2017, PhD enrollments in the country jumped by 50 per cent, and articles were written about the mad rush to attend university. In particular, the authors of these articles raised concerns about research relevance, quality, authenticity and originality.

Recently, mental health issues also attracted attention when authors of a study conducted among PhD students in two Indian public universities reported that 70 per cent of respondents suffered mild to severe depressive disorders. The cases were severe among students of economically weaker sections, those who earned less than 250 dollars a month or were less proficient in English. Despite this, the mental health of PhD students in India is still a stigmatized issue, where many deny that there is a problem. In my opinion, this is why those of us that feel able to speak out must do so. In this blog, I share insights into the challenges I have faced both at the start of my journey into academia and now as I begin to supervise students. I hope this is of some value to PhDs and new academics in India and beyond.

Mental Health Challenges as a PhD Student

While completing a Masters degree in management, I decided to pursue a career in academia. I felt being an academic resonated with my ability and identity, and I thought I knew what it would be like. This made me comfortable and confident about the profession. In higher education in India, a PhD is an essential qualification for academic jobs. So, my natural next step was a PhD program.

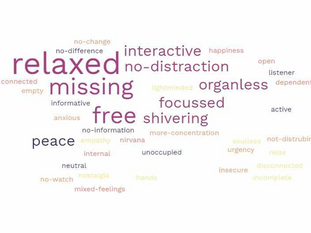

In retrospect, the training and the opportunities that followed changed my life forever. When I joined the program, I believed I had a fair idea of the requirements and expectations, given that my father is an academic and I have been raised among people from the same profession. Even this insight was not enough to fully prepare me; when I reflect, I had only a faint idea about the challenges, especially those relating to mental health. I was unprepared for the range of intense emotions I was about to experience: from confusion to uncertainty, to fear and angst, vulnerability and loneliness.

The first factor that impacted my mental health was going from a state university (where I studied for my Masters degree) to a top technical institution. I remember feeling out of place and anxious in my supervisor’s office on my first day. The institution’s brand was intimidating, and it took me quite some time to adjust to the environment. I now relate to those feelings as the imposter syndrome – feelings of self-doubt, under-achievement and incompetence. Initially, it instilled fear in me, and I had to muster courage to face people every single day. I also started observing some patterns. There were groups, and everyone was expected to be a part of one group. There was division and bias based on gender, caste, region, colour, economic background and religion, but no one was willing to discuss these divisions and biases openly. Culturally, in India, we are raised with very strong value systems that influence our decisions. It therefore can take a long, long time and a great deal of self-actualization to be able to make decisions without the cognitive biases ingrained into our culture and value systems– something some did not feel the need to address.

Then there was the uncertainty. There were very few milestones throughout my PhD and hardly any structure to follow. My supervisor took the role of a facilitator meaning that contact time and assistance was decided mutually and there were frequent meetings. But the PhD journey slowly and steadily unfolded itself over time, at the outset it appeared like a mountain I would be unable to climb. Further, my roles and responsibilities were not defined. One day, I would be assisting with teaching. On another day, I would be co-organizing a conference. There was work related to admissions, training, seminars, outreach, research and teaching assistance, and the journey was very lonely. Unlike other academic degrees, the pace was in my hands to a great extent. There were no classes, and hence no classmates. There were peers, colleagues, and co-authors – each had her own story. Amid these challenges, one that stood out was about power. One of my students recently explained it very well – a PhD is neither a course nor a job; it is somewhere in between. While the requirements and expectations are similar to a job, neither the designation nor the benefits are equivalent. I never dared to say ‘no’ to any work fearing that it might negatively affect my progress. I feel most of the students are in the same situation.

The pressure kept on building for days, weeks and months. I started exhausting myself through overworking. I woke up early to reach the laboratory. I would work until the late evening and follow the same routine seven days a week. By the middle of my third year, I was on the verge of burnout. My eyes would always be deep red. I would go to a physiotherapist and come back tired. My brain would continuously work and eventually, I would feel numb and exhausted. The physical and psychological pain kept increasing and there seemed no way out.

Seeking Psychiatric Help

In October, I went home for Diwali; the festival of lights for the Hindus in India that celebrates the triumph of good over evil. It is a significant occasion for families to meet. As we all celebrated the festival, my parents sensed something was wrong. They could gauge sadness, melancholy and restlessness in my eyes. I am still not sure how but they felt that I needed help. Probably, it was something to do with their life experiences. They convinced me to visit a psychiatrist. The visit was helpful; it enabled me to take a moment and slowdown. Ultimately, I was recommended anti-depressants for two weeks. I could sleep well, and being able to sleep well broke the pattern of overwork and gave me the strength to start again.

Back on campus, I visited a doctor appointed by the institute. He was aghast that I had been recommended medication. He said that almost 50% PhD students visited him and what I felt was very normal for a PhD student. I was taken aback. The visit also instilled fear in me about the side-effects of medication. Reflecting, he was likely only building further stigma around medication. I never shared this incident with anyone. I didn’t want to be labelled as ‘weak’, ‘mental’, or ‘depressed.’ I had it all in the conventional sense of the world, and I didn’t want anyone to think I wasn’t happy.

While growing up, my friends and I found our heroes in Bollywood. They were always larger than life, never vulnerable or scared. They would defeat a dozen villains single-handedly and come out victorious. I believe that stereotypes can sometimes be harmful because vulnerability is rarely seen. Vulnerability is not shown to be beautiful or powerful or strong. As such, I always attempted to be like these heroes – strong, robust, and resilient. And yet, my real life involved navigating academia and all its challenges; the student-supervisor relationship, employee versus student debate, lack of structure and uncertainty, cognitive biases, diversity and equity issues, peer pressure, jealousy, pride, power and politics. I found that these systemic issues were not something I could just power on through.

Creating Change

Now, as a PhD supervisor, I see things differently. In many places around the world, academia is anything but rosy. Often students seem scared and helpless, trying to figure out their paths, just as I did. For those in the early stages of their careers, there is considerable pressure to publish and climb the career ladder. Personally, I believe that those of us in academic positions need to speak up about mental health concerns so we can help the next generation of academics. There is no magic wand, I feel it’s just that our students deserve respect and need support. They need to be treated well, listened to, and given answers.

As a supervisor, I find balancing my mental health challenging in different ways. -The time available for supervision is shrinking, and expectations are mounting. I have found that metrics and quantification of productivity are increasing, fueling organizational politics like never before. Amid all of it, there is a lack of awareness and infrastructure for mental healthcare, and those who live with mental illness are still often seen as weak. According to the National Mental Health Survey, although 150 million Indian need mental healthcare services, less than 30 million are seeking these services. The number of mental health specialists per 100,000 people ranges from 0.1 to 9.73 in different states.

Navigating academia in India is tough. If you experience a mental health concern, to begin with, you may not recognize that you are unwell. If you know you are struggling, you may be unable to accept it. If you accept it, you may not be able to share it. If you share it, others may not believe you. If someone believes you, you may not know where to find help. If you get help, even then it might be a challenge. I was lucky to be born into a family that could recognize my need for help; everyone is not fortunate like me. So, where do we begin? Do we fix the culture first, or the rules or the infrastructure? All I know is it is time for change. In the words of Robert Frost: “We have miles to go before we sleep.” Though, for now, I think I will take a pause and rest a while.